Fortunately, electrodes made of metals such as gold, silver, or bismuth can catalyze the transformation of CO2 to CO. Bismuth has advantages over other metals, including (1) working as well, if not better, than gold, (2) being readily available in large quantities because it is a by-product of lead mining, and (3) costing nearly 350 times less than gold per gram. Because of these advantages, bismuth metal is under consideration for CO2conversion, but the molecular details of the process are not well understood. To gain a deeper insight into the process, the group recently began investigating the use of bismuth metal in CO2 conversion catalysis on the molecular level.

The first step was acquiring a disk of bismuth that could be used to produce bismuth atoms. A trip to see Hans Green in JILA’s instrument shop resulted in the discovery of some 20-year-old, high-purity bismuth shot (1–2 cm pieces of pure metal). Green added the shot to a tailor-made disk-shaped aluminum mold and heated it up on a hot plate. After the disk cooled, Green machined it to provide a smooth surface to make it possible for the laser beam to blow off atoms one by one.

The second step was to begin a study of the chemistry of CO2 conversion by looking at how to transfer an extra electron to a CO2 molecule. This step costs a lot of energy unless a catalyst is used.

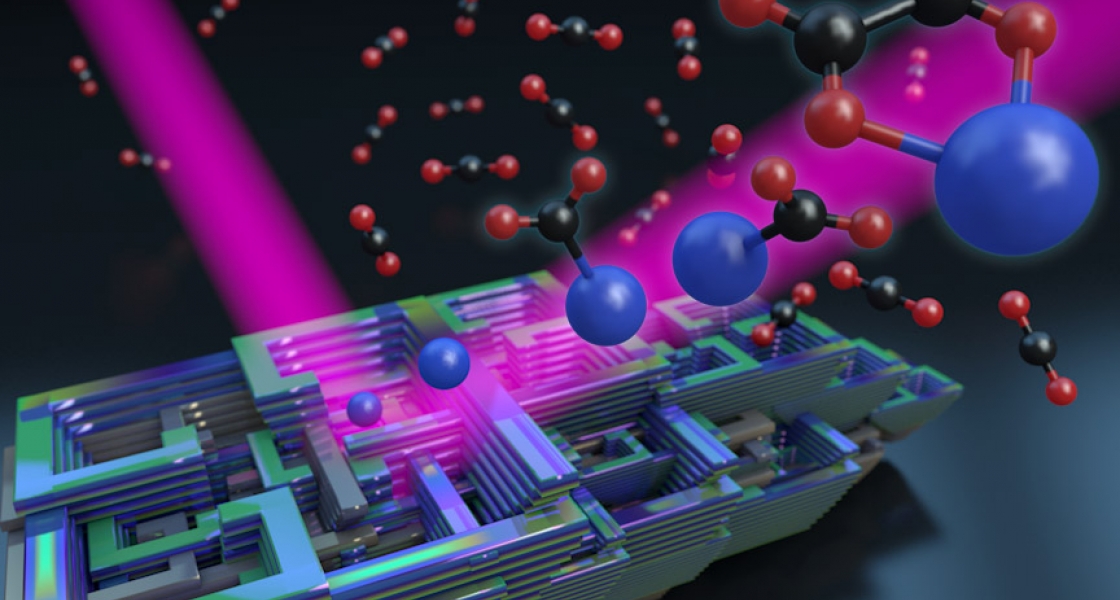

“We study how a few CO2 molecules bind to a single charged bismuth atom,” Thompson explained. “The reason we do this is that actual electrochemical cells are very complex systems, so we’re trying to simplify the system as much as possible so we can get at the heart of the interaction.”

What Thompson and his colleagues learned from studying their bismuth-CO2 cluster model system was that a CO2 molecule docked onto a negatively charged bismuth atom through the carbon atom. The chemical bond between the bismuth atom and the CO2then allows an electron to spend about 65% of its time on the CO2 molecule. By the time the researchers positioned approximately four CO2 molecules around the bismuth–CO2molecule, the extra electron was almost completely transferred to the attached CO2molecule.

But when a fifth CO2 molecule was added, suddenly two CO2 molecules bound to the metal atom. The two CO2 molecules also formed a carbon–carbon bond with each other, forming a molecule called oxalate. This is similar to processes in a real electrochemical cell, where oxalate can also be formed. This is a significant finding because it shows that the Weber group’s cluster model can be used to learn something about processes in electrochemical cells. And, with some additional work, there’s a good chance this model system will also produce CO!

The researchers responsible for this intriguing work include graduate student Michael Thompson, Fellow Mathias Weber, and group collaborator Jacob Ramsay (University of Aarhus, Denmark).––Julie Phillips

The Physics Frontiers Centers (PFC) program supports university-based centers and institutes where the collective efforts of a larger group of individuals can enable transformational advances in the most promising research areas. The program is designed to foster major breakthroughs at the intellectual frontiers of physics by providing needed resources such as combinations of talents, skills, disciplines, and/or specialized infrastructure, not usually available to individual investigators or small groups, in an environment in which the collective efforts of the larger group can be shown to be seminal to promoting significant progress in the science and the education of students. PFCs also include creative, substantive activities aimed at enhancing education, broadening participation of traditionally underrepresented groups, and outreach to the scientific community and general public.

The Physics Frontiers Centers (PFC) program supports university-based centers and institutes where the collective efforts of a larger group of individuals can enable transformational advances in the most promising research areas. The program is designed to foster major breakthroughs at the intellectual frontiers of physics by providing needed resources such as combinations of talents, skills, disciplines, and/or specialized infrastructure, not usually available to individual investigators or small groups, in an environment in which the collective efforts of the larger group can be shown to be seminal to promoting significant progress in the science and the education of students. PFCs also include creative, substantive activities aimed at enhancing education, broadening participation of traditionally underrepresented groups, and outreach to the scientific community and general public.